Life in a Spiritual Community – Nayawami Shivani Narrates

My first childhood ambition was to become a rabbi. Actually it was the scriptures that attracted me, and the sound of the sacred language. At the age of six I began to study Hebrew and very soon knew all the prayers by heart. But I was never called to recite in front of the congregation, because in the orthodox Jewish tradition women are not called to read from the Torah. Nor can they become rabbis, or even, as I discovered when I was 12, can they receive initiation into the body of worshippers (bar mitzvah).

So I turned my attention to another calling: to become an advocate for truth and justice. Applying myself to my studies, I won admission into a Washington, D.C. law school. Although I had dedicated years of my life to reaching that point, I was disillusioned from the first day.

I well remember the course in criminal law, one that had a great attraction for me. In his first lecture, expounding on the theme of legality and morality, the professor remarked that anyone who believed in such a thing as natural law, or in a correlation between morality and legality, was in the wrong university: they should rather be enrolled in a seminary. Since that door had already been closed, there was little I could do but plod ahead, hoping things would improve.

In addition to classes and a mountain of homework, I also worked as a legal assistant in the offices of several private attorneys, both to gain experience and to pay for my education. Again I was disillusioned when I discovered how many and how significant were the compromises required in order to “win” a case.

Completely discouraged, I left law school after two years and began to search for some other ideal to which I could totally commit my heart and my energies. This was my real desire: to have a life that challenged me completely, that engaged me totally on all levels of my being. It became impossible for me to even imagine living in a society whose values were superficial and materialistic. I dreamed of being a pioneer, of helping create a new way of living.

I left Washington, D.C., said goodbye to my family in Pittsburgh and “hit the road” with a few possessions in a backpack and very few dollars in my pocket. I was 23 years old and it was the summer of 1968. I had enough chutzpah and sense of adventure to hitchhike across the country, picking up jobs here and there when necessary. In Colorado I met up with the hippies and flower children, and continued travelling around the country with a pet Spider monkey, Ulysses, on my shoulder.

With the approach of winter, Ulyesses and I settled down in Palo Alto, where I found a job as a legal aid and secretary to a private attorney and where I continued my spiritual search at the “Free University.” But what my heart was looking for I couldn’t find in encounter groups or gestalt sessions. Deep down I knew that life had something special for me, but I also knew that I wasn’t finding it. I wrote in my diary at that time: “I think I need a Guru to show me the way.”

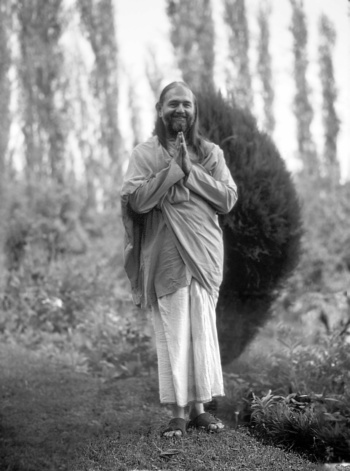

Swami Kriyananda

Swami Kriyananda

I first heard of Swami Kriyananda when I was in a small aircraft flying over the San Francisco Bay. My friend, the pilot, was telling me about the marvelous yoga teacher he had found in Palo Alto—an authentic yoga master called Kriyananda. I accompanied him to his yoga classes and was not a little surprised to discover that the yogi was an American who began each class by playing the guitar and singing one of his own compositions. His voice, and the way he lead the postures were very soothing. Inspired by his talk on vegetarianism, I stopped eating meat and, miraculously, stopped smoking as well.

At the next to the last class, Kriyananda told us about thespiritual community he was starting on land he had recently bought in the Sierra Nevada foothills. He had just finished writing a book about cooperative communties and he invited the students to read it and to come help him build the community.

I read the book in one sitting and immediately wrote a letter to Kriyananda’s assistant, John Novak, requesting to come for two weeks in the summer. I soon received a positive reply and began to make plans for another cross-country hitchhiking journey, with a first stop at Ananda Meditation Retreat.

Spiritual community

I arrived at 3:30 p.m. on the afternoon of Sunday, June 22. Ulysses had long since found another home; but I had again a few possessions in my trusty backpack, along with a sleeping bag, $100, and a copy of Autobiography of a Yogi which a friend had given me as a going-away gift. I had yet to read it.

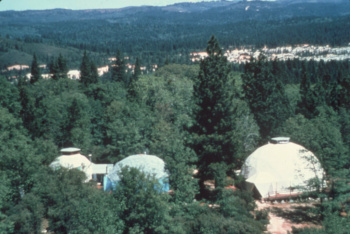

Three Domes – Ananda Village

I presented the letter from John Novak to a calm-mannered elderly man called Satya, who kindly welcomed me and showed me around the premises: the temple dome, the kitchen-dining room dome, the office dome, and the bath house (not a dome). I found a friendly pine tree to sleep under, and spent that afternoon gathering pine needles for a mattress.

Each morning Satya rang the bell on the temple deck and soon thereafter he began to lead us in the energization exercises and yoga postures, followed by meditation. All too often I wouldn’t hear the bell, especially when the wind was blowing in the wrong direction. So I moved my bag onto the temple deck and slept there, to be sure not to miss the morning practices.

Having spent 22 of my 24 years in school, I hadn’t learned any practical skills, other than how to pass examinations. I was given work in the kitchen, cleaning and cutting vegetables, which left me adequate time to pursue yoga practices and spiritual reading.

The few residents were mostly recent arrivals. The previous summer the buildings had been constructed, and only two people had braved the winter weather at 2500 feet. Now regular weekend programs were being offered and young people were starting to come and take up residence. In addition to Satya, there was Binay and also Jaya and Sadhana Devi. The weekend after I arrived Swami Kriyananda moved up, having finished his yoga classes, and soon thereafter his two assistants, John Novak and Sonia Wiberg (Jyotish and Seva) also came. Devi arrived about one week after I did.

Meditation

Although I had studied hatha yoga with Kriyananda, I had not taken his course in raja yoga. At Ananda I observed how peaceful and happy others were when they meditated, and I soon developed a desire to learn. After some weeks I made my decision: today I will learn to meditate. That afternoon I went to Kriyananda’s dome and somewhat timidly knocked on his door. A weak “Come in, please” resulted, and when I entered I realized that he was sick in bed with the flu. Excusing my intrusion, I was about to beat a hasty retreat when he asked me, “Why have you come?” I answered, continuing to back up towards the door, that I was interested in learning to meditate, but that some other time would be fine. He responded to the effect that “this seems to be the chosen time, so let’s do it right now.”

Even though he clearly was feverish, he got up straight away, invited me to sit down, and gave me a complete lesson in the Hong Sau technique, including an inspiring explanation of how the energy currents flow around and through the astral spine. I left his house with much gratitude, and with great enthusiasm I went immediately to the temple to try the technique on my own.

Looking back to this moment from a distance of nearly thirty years, I realize more clearly how much I learned that day. Beyond the precious gift of the meditation practice itself, I saw in action an example of selfless service: Kriyananda did not permit his indisposition to hinder the spiritual service he was being called upon to render. His response had been unhesitating; the state of his health had not been an obstruction.

Young Shivani

I saw something else that day in the way that Kriyananda responded to my request that I have seen on countless other occasions, an attitude that I consider one of the hallmarks of his spiritual legacy: that when the moment is ripe, that is the best time to act. Moments of true inspiration are indeed fleeting, and when we ponder and reflect and weigh and balance, the inspiration is often gone, and with it, an opportunity missed.

I try to remember the lessons of this day whenever someone asks me for help or when something unexpectedly presents itself in my life. For me, this is one of the deeper meanings of the Indian proverb: the guest is God.

In that first year or so Kriyananda led many of the energization, yoga and meditation practices and gave all of the Sunday services. There were some special features of the Sunday program that have not survived the years, but in which residents and guests eagerly participated. The morning began with a “strolling kirtan,” initiated by Satya after he rang the wake-up bell. Strolling through the grounds he would sing a chant and play the drums, thus calling the devotees to sadhana. The awakened ones would follow behind him, singing and perhaps playing hand cymbals. Arriving at the temple completely awake and with the name of God in our hearts, we began our morning practices.

An hour before the Sunday service was to begin, we gathered in a small clearing in the woods. Here a fire pit had been dug, with tree trunks placed all around it serving as seats. Kriyananda would arrive with his harmonium and lead us in a chant. Then he would light the fire, take a bowl of ghee, and pouring the ghee into the fire he would chant the Gayatri Mantra. The clarified butter, he explained, symbolized the pure aspirations of our hearts, which we were offering into the flame of devotion that they might become purer. Then he would chant the Mahamrityunjaya Mantra, throwing grains of rice into the flames after each repetition. The rice symbolized the seeds of our past karma which we were offering and burning in the flames of divine love and wisdom.

After the ceremony many of us stayed to meditate awhile, immersed in the vibrations of those holy mantras. As I mentally repeated these words, I remembered other holy prayers in another sacred tongue, and my soul was fulfilled.

First obstacles

Shivani first row, far right

I watched as my new friends grew rapidly in the path and as they received initiation into Kriya Yoga. I, too, longed to put on the white initiation clothes and enter the temple on those sacred occasions, but something was blocking me. Even though I knew I needed guidance, how could I possibly accept a Guru, someone who would be an intermediary between me and God? And how could a nice Jewish girl like me accept Jesus Christ?

Finally I sought Kriyananda’s advice, half afraid that he would say I must either accept Yogananda and Jesus or leave the community. My fears were totally unfounded, and his advice totally unexpected. “Why don’t you consider God to be your Guru. That should pose no conflict with your religious upbringing. Nor should it be difficult for you to accept the universal Christ Consciousness, the formless presence of God in creation. This is the real teaching of Sanatan Dharma and of Yogananda, and it should be even easier for you to grasp this, who have grown up with the formless God.” This was a completely acceptable answer for what I had considered an irresolvable problem.

In this experience what I most of all appreciated was Kriyananda’s sensitivity to my situation. He was honoring my past experience and helping me to build upon it. This respect for each person is also a hallmark of his spiritual legacy, the foundation of his teaching that “people are more important than things.”

That first summer ended with a full week of classes given by Kriyananda, which he called “spiritual renewal week.” Every morning after breakfast we gathered under the big oak tree next to the temple, where mats and cushions were placed on the ground and a chair placed for Kriyananda. Everything he talked about was new to me, much of it way over my head; yet it was all somehow familiar. Even the outdoor setting and the summer heat were familiar. I had heard these teachings before and done these practices. I had come home. Sitting there, listening to these wise discourses, I knew I had found the Truth and Justice I had been mistakenly seeking in the field of jurisprudence.

I spent the winter of 1969-1970 at the Meditation Retreat, while most of the others accompanied Kriyananda to the Bay Area to find work. At the outset it was Kriyananda who had earned the money to make the down payment on the land, and he continued to make the mortgage payments, inviting others to share this responsibility with him. It was at this time that Jyotish did the ground work for the incense business and Binay for the flower jewelry. I was among the very few who stayed and looked after things at the retreat.

Actually, there was very little to be looked after, and we had a lot of time at our disposal to lead the life of forest hermits. The larder was scant indeed, with a preponderance of powdered milk, whole wheat, barley and prunes. Since there was no income and no savings, we got by on bread, yogurt with prunes and grains.

Having been so accustomed to studying, I thought to delve into Sanskrit during the long winter months. When I asked Swamiji if he had a Sanskrit text he would lend me, he suggested that I rather read The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. I spent that winter in a tiny trailer a guest had left for our use, parked way out on Sunset Boulevard, absorbed with Ramakrishna and his disciples, meditation and hatha yoga practices and long, long silent walks in the woods. I spent days, sometimes weeks at a time in silence, which I found very comfortable and comforting. I was never lonely. Although part of me was thinking that I too should be in the city earning money for the mortgage, another part of me was very grateful for the chance to construct a spiritual foundation on which to build the rest of my life. As for the mortgage, my tree-planting days still lay ahead.

Renunciation

I had been at Ananda two years and the summer guest season and Spiritual Renewal Week were over. Kriyananda was enjoying a time of retreat and silence in his dome. One day as I was taking his mail to leave outside his door, I found him standing on the porch. When he saw me he asked: “What to you think about monasticism?” I was so surprised to hear him speak, and even more so hearing what he said, my mind froze and I couldn’t immediately respond. After standing there dumbly for a moment, I said: “You mean living like a monk?” “In your case,” he answered, “it would be like a nun.”

I had been at Ananda two years and the summer guest season and Spiritual Renewal Week were over. Kriyananda was enjoying a time of retreat and silence in his dome. One day as I was taking his mail to leave outside his door, I found him standing on the porch. When he saw me he asked: “What to you think about monasticism?” I was so surprised to hear him speak, and even more so hearing what he said, my mind froze and I couldn’t immediately respond. After standing there dumbly for a moment, I said: “You mean living like a monk?” “In your case,” he answered, “it would be like a nun.”

Even though I was shocked, I was not unprepared. I had been reading The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna and had been thinking seriously about the monastic life as a possibility for myself. Kriyananda said that I was welcome to think about it and speak with him privately if I wished.

Just at that time I had an interesting dream. I was working with others and we were making a wide road, using shovels to dig down and flatten the area. Someone approached me with this advice: “If you really want to make progress on this road, you need to cut off your right arm up to the elbow.” I replied: “But then I could only work with one arm and the work would be much slower.” He responded: “Actually, if you want to make really fast progress, you should cut off both arms.” At that point I awoke and began to meditate on what the dream could mean. The answer didn’t come quickly, but eventually I understood it to signify that I could make more rapid spiritual progress through a dramatic act of cutting off my ego, the thought that “I” am working. I took it as an indication that I should seriously consider joining the monastery.

I went to speak with Kriyananda and he told me about the monastic order he evisioned at Ananda. He explained to me the three traditional monastic vows, and how he saw them in the context of our community life. The one that gave me the most pause for reflection was obedience. I had never been very good at it, and I was always getting into trouble with “authorities.” He was very understanding and I’ve always remembered what he said: “I’ll never ask you to accept any spiritual advice I may give you, for I could be wrong. I would ask only that you hold it up to the light of your own conscience. In matters pertaining to the organization of the community, however, I would expect that you cooperate with me.”

Having understood that, I asked to be accepted into the new order. Some days later, seven of us met in Kriyananda’s dome for a simple initiation ceremony. There was Seva, Sadhana Devi, Satya, Binay, Jaya, John Blake and myself. In blessing John, Swami gave him the spiritual name Haridas; and when blessing me, he gave me the name Shivani, which he said means ‘renunciation’—s good name, I thought, for a nun. The order itself he called “The Friends of God.” During the ceremony Swamiji explained that of all the relationships that we can have with God, friendship is the most freeing. Even Master, he said, who worshipped God as the Divine Mother, said that friendship was the highest relationship, because it is completely unconditioned by the responsibilities inherent in other relationships. He mentioned Yogananda’s relationship with Krishna in the incarnation when Yogananda had been Arjuna.

This was in September of 1971, perhaps even on the 12th, which is Swamiji’s spiritual anniversary. He invited us to move our trailers and teepees onto his private land, which he called Ayodhya, the name of Lord Rama’s enlightened kingdom in ancient India.

After we had moved, we went to ask him for the guidelines of the new order: at what times should we meditate? should we have a temple in common or a separate one for the monks and the nuns? In answer to all our questions, he responded: “You decide. Find within yourselves the way that is most suitable.” As he must have anticipated, we did not always decide wisely, and we had ample opportunity to learn through our mistakes. Although he never actually participated in these “practical spiritual” decisions, his energy and his prayers were obviously guiding the work on a higher level.

Even though I was adverse to authority, there many times I wished that Kriyananda would set down some guidelines. It would have been easier to get up early and meditate long hours knowing it was required of us. Easier in the beginning, perhaps, but apparently that was not the kind of spirituality Master and Swamiji wanted from us. We needed to learn to meditate and serve because we loved doing it, not because we were obliged to do so.

And this is perhaps what I appreciate most of all about Swamiji and how he trains us: he creates the situations in which we can grow, and then throws us into them, knowing that we’ll either sink or swim according to the energy we put out. In all situations that I have observed, he gives each person the freedom to grow without the stifling weights of restrictions, or rules or conditions. He often quotes Master, saying: “too many rules ruin the spirit.”

And so the monastery and the community grew without too many rules, and with a great spirit. Swamiji invited the monastics to his house every week, where we meditated together and then listened to him speak about the spiritual qualities we were trying to develop. We tried our best, we struggled, and for the most part we swam. We worked hard to build up the community, and after work we came back to Ayodhya to meditate, study and get ready for another day of service. Others joined the order and soon there were 30 or 40 or us, serving in all of the areas of the community.

In the garden

My early Ananda experiences and spiritual growth are inextricably linked with our organic garden. Until I arrived at Ananda I had been undoubtedly a city girl, with very little experience of the great outdoors or, for that matter, of physical hardship. Yet even a short while of living amongst the ancient oak trees, walking long distances through the forest, swimming in the Yuba River and seeing the distant high mountains had a remarkable affect on my consciousness. I realized that my first spiritual lessons would come to me through nature.

Farming at Ananda Village – Early days

In 1970 Kriyananda invited Haanel Cassidy to move to Ananda and develop an organic, biodynamic farm on our new land. Haanel was already in his sixties, a long-time Kriya yogi and had considerable experience with biodynamic gardening in Canada and in Chile, where he had attempted to retire. Kriyananda offered him Ananda as his retirement spot, where he could practice Kriya and serve Yogananda by teaching us youngsters how to develop a self-sufficient farm.

I had never in my wildest dreams imagined myself working on a farm, slinging manure, driving a tractor or cultivating earth worms. Yet one cold day in January I presented myself to Haanel—which took considerable courage given his somewhat ascetic appearance, white hair, noble bearing and piercing blue eyes, and asked if he would accept me as a student worker in the garden he was to start that year. Skeptically looked me up and down and, as was his wont, with a few well-chosen words, he bade me meet him at the water tower (at the Meditation Retreat) at 7 a.m. on Monday morning. That was the first lesson: gardeners start at sunrise and yogis should be finished with their practices by then and ready to work.

It was a bitter cold Monday and Haanel took me to the apple orchard that we had inherited with the Farm. The trees had been neglected and hadn’t been pruned for years. He patiently taught me how to look at an apple tree and see the ideal form that God had given it—its main, or leading branch through which it grows tall; the best number of lateral branches to support its current size and the load of fruit it would bear. Then he taught me how to cut away everything that was extraneous to that essential form. And not just to hack away the unnecessary, but to liberate the tree from its burdens in a gentle and scientific way—each cut was angled so that it would quickly heal over and permit the life force to flow in a new direction. There was real poetry in Haanel’s approach to gardening and to life, and indeed he himself was an accomplished photographer, writer and singer.

We worked together that morning, he showing me which branches to eliminate and how to do it. Then he left me on my own for the afternoon, expecting me to do as much as possible. Not only were my hands frozen and barely functional, but also my mind was sluggishly trying to grasp the concept of helping the trees by eliminating a great part of each of them. By the end of the day I had begun to understand not only that the trees needed and were grateful for this work, but that I as well needed to be pruned of many useless ideas and habits if I wanted vigorous, new spiritual growth. In later years, when I began to study the New Testament, I could resonate with Christ’s words, “Every branch in me that beareth not fruit he taketh away: and every branch that beareth fruit, he purgeth it, that it may bring forth more fruit.”

Gardening in the early days of Ananda

Eight years I worked in our gardens, sunrise to sunset, spring, summer, fall and even into the winter, learning more about life and spirituality than books could teach me. Perhaps the most important lesson of those idyllic years was the recognition that growth is cyclic, and we need to work in harmony with its rhythms, irrespective of how we feel or what we want. How nice it would have been to take a summer vacation and go hiking in the high country. But in the extraordinary heat and dryness of Ananda summers, even one day without water would have been the death knell for the plants.

I clearly remember the year of the exceptionally long Indian summer. We had a large winter squash crop, and it was happily ripening, gaining more vitality with each passing day. But we had to closely watch the weather, knowing that we would have to harvest them before the first hard frost. A long rainy period ensued, with warm temperatures. But by then it was well into November and the frost could come any day.

It was in the middle of Sunday service when the skies suddenly cleared. A starrey and freezing cold night lie ahead. As we were filing out of the temple, I whispered to the other gardeners: it’s now or never—let’s skip lunch and get those squash inside! We worked well past sunset, but we didn’t lose a single one of them. When in later years I read in the Bible, “the harvest truly is plenteous but the labourers are few,” I remembered that day and could well imagine the labour needed to reap the harvest of God consciousness.

While the garden provided us with unpolluted, tasty vegetables, it didn’t bring money into the community, which was needed to meet the monthly mortgage payments. And so began the first phase of economic development and responsibility at Ananda, which can be called the “cottage industry phase.” The first of these small industries was the incense and perfumed oils business that Jyotish had developed in the Bay Area and brought to the community. At the same time Binay developed the wild flower jewelry business, and soon thereafter was added a macrame plant hanger endeavor.

Most of the gardeners spent half of the day in the fields and the other half day, as well as the winter months, in the incense business The “cathedral building” had been erected, next to the barn—a simple construction of curved wooden supports covered with heavy-gauge plastic, which kept the inhabitants dry but did little to keep out the wind or the cold. Winter mornings in the cathedral building are especially memorable. After having usually spent a pretty cold night in the teepee, we arrived to find the building no warmer than the teepee. The incense paste that the imported sticks were to be dipped into was solid enough to cut, and the perfumed oils were too sluggish to be poured. A good part of the morning was spent standing near the stove, warming ourselves and our materials. The building itself never really got warm, so we worked with old gloves that had the finger portion cut away. My most welcome acquisition of those early years was a pair of L.L. Bean felt-lined boots, which made a remarkable difference in my joie di vivre level.

While this indoor, repetitive work was not nearly as enjoyable as being outside with the plants, it was part of the challenge of being a pioneer. I had long lamented the materialistic and, to me, meaningless life that had been created, no doubt through untold sacrifice, by previous generations. The physical hardships were of little consequence to me, for I was now able to live one of my most cherished dreams—with my own hands and the sweat of my own brow to build a new way of life.

Outside employment

One winter in the early ‘70s our financial situation was so dire that we had to find outside employment for many of the residents. As Master often said: “Circumstances are always neutral; it’s the way we respond to them that makes them positive or negative.” This seemingly catastrophic circumstance gave me and many others to chance to do what Sister Gyanamata called “testing your spirituality in the cold light of day.” We were forced to leave our nest of spiritual security and measure our inner growth out “in the world.”

We learned that the Forestry Service was offering contracts for planting sapling trees in areas that had been clear-cut and burned. Anyone could enter a bid. Ours was the lowest bid to replant a large number of acres in northwestern California in an area called Happy Camp. We had, I believe, 12 weeks in which to complete the job. If we didn’t finish on time, we would be subject to a daily fine.

We were all tested during those weeks, which, while they got somewhat easier, were never a stroll in the park. As we were approaching the end of the time limit, and it became obvious that we wouldn’t make it, we called back to the community for reinforcements. By that time our bodies were exhausted and wounded, and divine intervention needed to come through other bodies. It’s hard to describe the relief we felt when four men arrived to help us finish the contract. Our spirits soared, our bodies felt renewed, and we finished on time! And we came back to the community with money in our pockets to contribute to the mortgage payments, and some hard-earned spiritual strength under our belts.

Christmas

My favorite time of the year was Christmas, and especially the period leading up to the long meditation. There was little work to be done in the gardens, because in most years they were buried under a thick blanket of snow. Life slowed down and everything got very quiet. Many of us took seclusion at this time, and remained in silence until the long meditation. The atmosphere at Ayodhya was remarkable—deeply peaceful and deeply joyful.

I used this time to learn more about the life of Jesus and his teachings. Yogananda’s commentaries on the Bible, published in the old Inner Culture and East West magazines, I found deeply inspiring and thrilling in their universality. The nice little Jewish girl was learning to be a Christian as well.

The Expanding Light didn’t exist then; all of the Christmas activities were at the Seclusion Retreat. Many years the snow was so heavy that the cars couldn’t make it up the final hill. So we would walk in, dry off, meditate, then walk out again. Swamiji, of course, was right there with us, holding his orange robes above his boots and plowing through the snow.

The social side of Christmas at Ananda was in those years touchingly simple: On Christmas day we met with Kriyananda in the temple and listened to Händel’s Messiah. Then we exchanged gifts we had lovingly made for reach other, which resulted in a temple full of discarded wrapping paper and ribbons. After the Christmas banquet, as had been Master’s tradition, Swamiji spoke to us, right in the dining room, about the deeper meaning of Christmas.

A conversation I had with Swamiji that especially stands out in my memory occured in the mid 70’s while we were at a spiritual conference in Vancouver, Cananda. Swamiji had been invited and introduced as “the father of spiritual communities,” an honorific he gently rejected with this interesting comment: “I don’t care all that much about cooperative communties; it’s people I care about, and their spiritual growth. That is the only reason I’ve created Ananda. And if ever in the future it is not helping people in this way, then it should not be perpetuated.”

Master’s Market

Later, as we were walking together, I asked him what he did see in the future for Ananda. His answer was unexpectedly specific. “For a while longer,” he said, “there will continue to be an implosion of energy, a building of our base at Ananda Village. But at a certain point there will be an explosion, and people will go out in small groups to start communties around the country and on other continents.” He mentioned, I believe, groups going to India, Australia and other places. “Ananda Village,” he continued, “is the model community, and it is taking my energy and presence to get it started. But once the model is established, it will be easier to reproduce it, and others will be able to do so.” I wondered if I would be sent out to some distant country, but at that time I was so content with my present that I didn’t really want to know about the future.

Shortly thereafter our city centers began to be established, first with Sacramento, then San Francisco, and, more than a decade later, also in Europe and then in Australia. Looking back to this conversation, I see that it was more prophetic than casual.

Marriage

The spiritual magnetism of the community was growing stronger all the time, and many devotees were being attracted, like bees to the veritable honey. An exceptionally large group arrived in 1974, and amongst them was my future husband, Arthur Lucki. He was already years on the path, a Kriyaban and, praise God, a building contractor.

I was very happy in the monastery, although I had my fair share of struggles. Never had I thought of leaving it, and certainly I had no desire to ever marry and have a family. Yet when Arthur proposed marriage, I referred the proposal to my spiritual father. I was absolutely and terrifyingly shocked when he suggested that I accept the proposal. His reasoning was straightforward and simple: spiritually I would grow more in a relationship than by staying in the monastery. There were other lessons I needed to learn now.

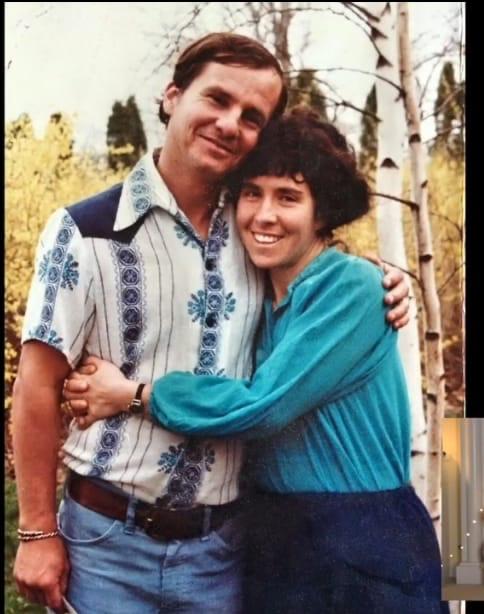

Shivani and Arjuna on their wedding day

Arthur and I were married six weeks later, on the 25th of April, 1975, under a full moon and extremely auspicious planetary aspects, in a very simple evening ceremony presided over by Swamiji. In his talk to us that evening, Swamiji broke the ice of solemnity by remarking: “This union should bode well for everyone, for is it not said that peace will come on earth when the lion of Judea shall lie down with the lamb of Christ?” And when during the ceremony he gave Arthur the spiritual name Arjuna, prince of devotees, I felt that Master himself was blessing our marriage. His talk that evening was about renunciate marriage, of living for God first and serving Him in the spouse, who should be considered a channel of God’s divine love.

For me, not very much changed in my life. I had the same work, the same dear friends, the same purpose and goal. And, in addition, I had a wonderful companion to serve and grow with. I have always considered this marriage a spiritual gift and a great blessing. It has never been the center of our life, but rather another part of our life which is dedicated to God. We consciously decided to forego creating our own family so that we would be able to serve Yogananda’s greater family, wherever that might take us. In 1985 the call came, and Swamiji asked us if we would like to serve in the newly-established center in Italy, where we have been ever since—living together with 50 other devotees in our European community.

Source: Reflections on Living, by Sara Cryer, 1998

Arjuna and Shivani

3 Comments

Dear Shivaniji,

Thank you for such a beautiful story of your amazing life. How blessed are the new generations which follow you on this spiritual path! 🙏

From Himalayas – on the way to Badrinath.

Arjuna

Om Sri Shivaniji

That was very inspirational , as is everything you do , a life well lived indeed

Love and blessings

Leon x

Dear Shivani, what a joy to read your beautiful story. And what incredible work you have done for Master and for Swamiji.

Jai Guru,

Surya.